One of the main defences raised for the use of South Sea Islander labour in the Bundaberg region is that by the time its sugar industry took off, the Pacific labour trade had been largely cleaned up.

The kidnappings, aka “blackbirding”, were supposedly history, due to stricter legislation and tighter government oversight. But is this true? How did recruiting really occur in those years?

Well we do have relevant first-hand accounts, from one of the hands at least. In the last post, I mentioned that the first ship to bring South Sea Islanders directly to Bundaberg was the schooner Lucy and Adelaide, which arrived in April 1879 carrying 88 new recruits.

According to Wikipedia, a schooner is a “sailing vessel with fore-and-aft sails on two or more masts, the foremast being no taller than the rear mast(s).” Pictured here is another labour schooner, the 100-ton Fearless, which ran from 1883 until it was wrecked in 1902 (John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland).

It so happens that one of that ship’s captains, William T. Wawn, wrote a book about his experiences, called The South Sea islanders and the Queensland labour trade: a record of voyages and experiences in the western Pacific, from 1875 to 1891 (S. Sonnenschein & co., London, 1893). The whole volume is available online at the Open Library.

Needless to say, it’s very one-sided. Wawn dedicates his work to the sugar planters of Queensland, who, among other noble achievements, “have done more towards the Practical Civilization of the Cannibal and the Savage than all the Well-intentioned but Narrow-minded Enthusiasts of the Southern Pacific.”

He rails against any critics of the labour trade, including missionaries, politicians (or ‘Political Place-hunters’), and “Exeter Hall” (a euphemism for the British Anti-Slavery Society).

And as you’d expect, it’s rather racist. Not just towards Islanders either: he also doesn’t like the French and the Germans, and even the Scottish get a rather harsh treatment.

Another contemporary labour schooner of a similar size, the 82-ton Mystery. In his book, Wawn describes this ship’s exploits too, including the trial of its Captain Kilgour for forcefully recapturing one of its boats (photo circa 1870-1880, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland)

Now Wawn actually took over as master of the 89-ton Lucy and Adelaide on its second Bundaberg voyage, starting in May 1879, but I feel it’s not too much of a stretch to suggest that his account is representative of the practices of the time.

Unfortunately, his records of that trip are rather uneventful, the highlights being a near ambush of one of his boats, only averted by the presence of the main ship; encounters with dastardly German and French recruiters that suggest to even him “a concealed system of slavery”; and rough seas off the tip of Fraser Island.

Perhaps more enlightening is the account of his first assignment in 1875 onboard the 115-ton Stanley, in which he sets out his standard recruiting procedure, as well as his opinion on allegations of kidnapping. Again apart from the activities of French or German recruiters, he claims that these were mostly due to a misunderstanding of language.

That whole section is worth reading, so I’ve quoted it in full below – click through after the jump to read more.

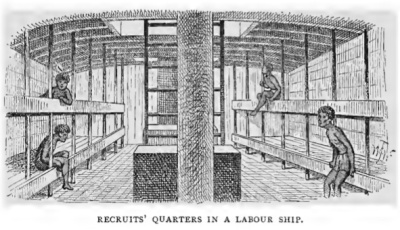

A sketch from Wawn’s book of the accommodation for South Sea Islanders onboard a recruiting ship. This lower deck, on top of the ship’s iron ballast, was fitted with two six-foot wide shelves for sleeping, extending the whole length of the hold. A bulkhead separated it into two sections, with the smaller one, accessed only from an outside hatch, for women.

Our boats, two in number, were each pulled by four islanders, having a mast stepped well forward when required, and a standing or “Spanish” lug-sail, the handiest rig with an island crew. The white man in charge used an eighteen-foot steering oar generally, but rudders and tillers were provided in case of running any considerable distance under sail in a sea-way. Each native boatman was armed with a smooth-bore musket, cut short so as to lie fore and aft on the beat’s thwarts under the gunwale, to which was nailed a long strip of canvas, painted, and hanging down to protect the arms from the salt spray. The whites — the recruiter in one boat, and the mate and G.A. in the other — had revolvers and Snider carbines. The smooth-bores of the boatmen were, a few years later, changed for Snider carbines, and the whites generally adopted the Winchester. Each boat carried a “trade box,” containing about a dozen pounds of twist tobacco, two dozen short clay pipes, half a dozen pounds of gunpowder in quarter, half, and one pound flasks, some boxes of military percussion caps, a bag of small coloured beads, a few fathoms of cheap print calico, a piece (twelve yards) of Turkey red twill, half a dozen large knives, with blades sixteen or eighteen inches long, the same number of smaller knives, half a dozen fantail tomahawks, a few Jews’-harps, mirrors, fish-hooks, and other trifles. Paint was then in frequent demand. For this we provided a tin canister of vermilion powder and some balls of Reckitt’s washing blue. On the thwarts amidships, along with the mast and sail, lay three or four Brown Bess muskets in a painted canvas bag ; good serviceable weapons, despite their age. The cheap German fowling- piece, however bright and new, was of no use to us. Tanna men, especially, were very particular about the guns having “TOWER” on the locks. They knew that these would bear a big charge. I have seen a Tanna man load one with powder enough for three charges, and ball on top, fire it off, and, when the gun kicked him over on his back, jump up again and shout, “Remassan! Remassan!— Good! Good!” He would buy that gun, and think he had the best of the bargain by a long way. But a Tanna man would not look at a smooth-bore now. Nothing, nowadays, will go down with him but a repeating rifle.

Those Brown Besses were intended as presents to the recruits’ friends. We were not frequently called upon to give guns then, and one gun would satisfy two or three parties. A knife and a tomahawk, a handful of beads, ten sticks or about half a pound of tobacco, a few pipes, and a fathom of calico, were considered sufficient for man or woman. But the demand for firearms was rapidly increasing, and, two years after this, I had to give a musket, as well as tobacco and pipes, before a man was allowed to leave the beach.

This custom of making presents to recruits’ friends has been eagerly seized upon by our opponents as proof that we really bought the recruits — that the latter were simply slaves, probably captured in war ; which is simply absurd. New Hebrideans never spare their enemies in battle, or make prisoners of the men. Slavery is unknown to them ; they are not yet sufficiently advanced to appreciate it. The theory that recruits are sold by their chiefs might be true to a certain extent, were it not that the power of the chiefs in these islands is extremely limited, far more so than it is among Polynesians, as in Samoa and elsewhere. But here each village constitutes a tribe, possessing its own chief, whose territory is measured by yards, not by miles.

The fighting power of a New Hebridean tribe is rarely more than twenty to eighty men. Consequently, if a warrior elects to go to Queensland, his departure is felt as a serious loss, to make up for which it is only natural that the tribe should require a musket, powder, and ball. Besides, you will get no article or service from a South Sea Islander without paying for it. Your necessity is his opportunity. To take a recruit in the presence of his friends without “paying” for him, however willing to go he might be himself, would be, at any rate, extremely dangerous.

Owing to their limited knowledge of the English language, such terms as “buy,” “sell,” and “steal,” have a wide and comprehensive meaning. “You buy boy?” is often the first question asked of the recruiter when he arrives at a landing-place. This simply means, “Do you wish to engage boys ?” “Boys,” as elsewhere, signifies men of any age. The term “steal” is also frequently misunderstood. If you take away a recruit from his home without “buying” or “paying” for him, — that is, without making presents to his friends to compensate them for losing him, — they will say you “steal” him.

In 1879 a woman, Betarri, came on board the Stormbird on her own account, and was engaged. Owing to subsequent events no present or “pay” was sent on shore. She afterwards told the wife of her employer, Mr. Monckton, of Narada plantation, Maryborough, that “Captain he steal me,” which the lady of course interpreted literally.

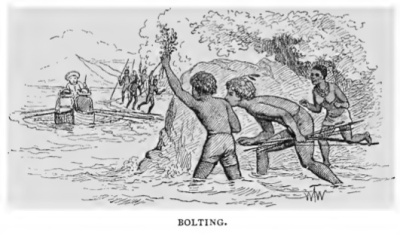

When it could be done conveniently and with safety, I have generally sent the “pay” ashore to the friends of any recruit who has joined my ship without their consent. Some “boys,” who have already served one term of three years in Queensland, are, however, too knowing for their countrymen, and make a bargain for money on arrival in port, varying from 10s. to £2. These have to get away quietly, of course, and they are said to be “Stolen.” By sending the pay for a runaway recruit on shore, any danger to the next comer will probably be averted.

This free use of the term “steal” amongst the islanders accounts for numbers of unfounded charges of kidnapping made against us. But kidnapping has been occasionally perpetrated in these waters, and was, even at the time I write of.

Previous to the annexation of Fiji, in 1874, recruiters from thence never missed an opportunity of “wooling ’em.” Many a canoe was run down, and its occupants saved, to work in Fijian cotton-fields. Australians will remember the Carl and Daphne. In 1872, at Bonape, in the Caroline group, I was, for a few hours, on board the Carl, then on her most notorious cruise, and I heard some of the crew boasting of their exploits. Even of late years — in 1884 — we had the Hopeful case ; and I know, from personal experience, that one at least of the prisoners in that affair richly deserved the fate meted out to him. Apart from the immorality of such a proceeding, kidnapping would be extremely impolitic on the part of a recruiter who expected to be engaged for any length of time in the labour trade. One case of kidnapping would spoil the captain’s, the recruiter’s, and the ship’s reputation on the islands, and the friends of the kidnapped man would not fail to kill the offenders at the first opportunity.

I mentioned that, in 1875, kidnapping was still occasionally heard of. I never witnessed it ; but, from the reports of natives all over the New Hebrides, I have very good reason to believe that men were often carried off forcibly by French and Samoan vessels, between 1875 and 1883. One could only expect outrages to be committed by the crews of these ; for, although the French vessels carried an officer whose duties were similar to those of our Government agents, I never saw one of them accompany his boats to the shore. The French boats were invariably manned and officered by Polynesians only. As for vessels out of Samoa, I may cite the Mary Anderson by way of illustration. She flew the British flag, was commanded by a foreigner who held no certificate except a licence to recruit from the British Consul at Samoa, and was employed to collect labourers for German planters. This vessel carried no Government agent, and the master alone had full control over the recruiting.

William T. Wawn, The South Sea islanders and the Queensland labour trade: a record of voyages and experiences in the western Pacific, from 1875 to 1891 (S. Sonnenschein & co., London, 1893), pp. 8-13.

Has anyone heard of William Bonar from New Zealand who lived in Roratonga? I read somewhere that he fell in with- sic- Bully Haines.

Would like more information. Thanks.

I’m focusing on ships recruiting South Sea Islanders to work in Queensland, and I haven’t seen any mention of him in that context. However, this site mentions him living in the Marshall Islands, as did Bully Hayes: http://www.micsem.org/pubs/articles/historical/bcomber/marshalls.htm. Also, there’s a death notice in the Auckland Star from November 1905, via the National Library of New Zealand.

Actually, here’s a more detailed death notice: http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=AS19051123.2.38&l=mi&e=——-10–1—-0–

You’ve provided some rather interesting material on William T Wawn. I became aware of his book via Mark Twain, who mentions it in relation to some missionary pamphlets on the Queensland Labour issue. I’m curious, do you think Wawn was honest in his description of his labour trade activities? Actually I’ve been working on a video of Wawn’s first voyage on the Stanley, using Google Earth tours to provide the main material. My narration is fully from Wawn’s book. As well as some other effects and nicities. It’s my impression that he was a pure capitalist and much like capitalists today – people are commodities. The condition of the islanders he seemed to deal with strike me as very much like our migrant agricultural workers here (I’m in California) today.

That’s fascinating—I had no idea that Mark Twain had mentioned Wawn!

I have no solid reason to doubt Wawn’s account of his activities, especially considering he is so self-righteously judgemental of others’ misdeeds. And although, as I mentioned, there were language problems that would have meant many of the recruits didn’t know what they were getting themselves into, he’s definitely convinced that he was in the right.

But that’s where we differ from him, as the trade in total was hugely exploitative and devastating to the island cultures. You’re right to view it through the lens of capitalism—his dedication, which praises the sugar planters for civilising “the cannibal and the savage”, makes it clear what he thought of the people he was trafficking, and how he believed that using them as cheap labour was in fact for their own good.

He also writes that the planters “spent the Best Years of their Lives and Millions of Money”—which is pretty much the most flattering way to view people who were really only interested in making ‘Millions of Money’.

How it compares with modern migrant labour is a lot harder to say, because expectations of labour conditions are very different, and racism is much less overt. I’m not saying there aren’t still problems, but let’s not forget that people like Wawn railed against anti-slavery activists—we’ve come a long way from that sort of thing.

You might also be interested in my post on similar labour controversies in modern Australia: https://bellsinequality.wordpress.com/2013/04/01/some-things-havent-changed/.

Just to let you know, I’ve completed my video of Wawn’s voyage of 1875 and published it on YouTube. It’s accessible through my own website at http://bscottholmes.com/content/william-t-wawns-first-voyage-aboard-schooner-stanley

Still in need of editing it should nonetheless be of some interest to those that can sit still for 1 hour and 12 minutes.

Well done! I look forward to watching it – it’s nice to be able to follow his voyage, and get a glimpse of what Pacific life was like so long ago.